A millenium ago, when the Maori first arrived, the Banks Peninsula was heavily forested, mostly in red beech trees with evergreens (not the ones we know, but rather from the family Podocarpaceae that are mostly native to New Zealand). In 1838 Jean Langlois, the captain of a French whaling ship purchased from local Maori what he believed to be the entire peninsula for goods worth about 1000 francs. This deed became the starting point for a muddied but determined effort by the French to start a colony on the peninsula. Langlois sailed home to France to make arrangements and recruit settlers. However, while the hopeful French settlers were on their way, the English established sovereignty over the whole of the north and south islands with the treaty of Waitangi. On August 11th, 1840, six days before Captain Lavaud was to arrive with a group of Frech and German settlers, the British flag was raised in Akaroa. However, the settlers stayed, planted gardens that included fruit and nut trees along with those roses that survived their journey. In 1843, an agreement was reached under which the French relinguished all claim to jurisdiction of the settlement and were placed under British law. The first British arrived in 1850 and what is now the town of Akaroa was established with the French at the north end and the British at the south end.

A millenium ago, when the Maori first arrived, the Banks Peninsula was heavily forested, mostly in red beech trees with evergreens (not the ones we know, but rather from the family Podocarpaceae that are mostly native to New Zealand). In 1838 Jean Langlois, the captain of a French whaling ship purchased from local Maori what he believed to be the entire peninsula for goods worth about 1000 francs. This deed became the starting point for a muddied but determined effort by the French to start a colony on the peninsula. Langlois sailed home to France to make arrangements and recruit settlers. However, while the hopeful French settlers were on their way, the English established sovereignty over the whole of the north and south islands with the treaty of Waitangi. On August 11th, 1840, six days before Captain Lavaud was to arrive with a group of Frech and German settlers, the British flag was raised in Akaroa. However, the settlers stayed, planted gardens that included fruit and nut trees along with those roses that survived their journey. In 1843, an agreement was reached under which the French relinguished all claim to jurisdiction of the settlement and were placed under British law. The first British arrived in 1850 and what is now the town of Akaroa was established with the French at the north end and the British at the south end.

With the settlement of Akaroa, the forests on the peninsula was seen as a source of timber needed for the burgeoning city of Christchurch. By the end of the 1800s, less that 1% of the original forest remained. You can see the result in the photo below. There is a sheep pen in the foreground, set on hillsides used as pasture occasionally broken by stands of trees.

As the forests were cleared, the land was planted in a variety of grass that the English call cocksfoot. The resulting meadows were used both as a source of cocksfoot seed and as pasture for cattle. With the cattle came many dairies. Today most of the cattle are gone, replaced by sheep.

This is a lot of background to explain why we spent the day hiking through the Hinewai Reserve. This nature reserve is an effort, covering over 3000 acres, to protect and restore native vegetation and wildlife in this section on the southeast part of the peninsula.of very small part of the reserve consists of old growth forest, the rest of moving in the direction and should achieve that state in several hundred years.

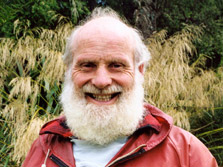

Much of the energy behind this effort is that of a botanist, Hugh Wilson, who has been working on it since its inception in 1987, and who we met cutting grass to make passable one of the trails on which we were hiking. He is an incredibly interesting and obviously quite energetic gentleman.

Much of the energy behind this effort is that of a botanist, Hugh Wilson, who has been working on it since its inception in 1987, and who we met cutting grass to make passable one of the trails on which we were hiking. He is an incredibly interesting and obviously quite energetic gentleman.

Because hiking through the reserve had been recommended by several sources, and becuase this history made the effort that the reserve embodies seem interesting we decided to spend the day hiking the reserve. Although one of the shorter options might have been preferable, we opted for the trails that loops around one of the two major catchments that make up the reserve — the second catchment has no trails in it. This loop trail turns out to be about 10 miles long with about 1600 feet of altitude loss/gain, much of it quite steep. It is true that we need to build up our strength for the Milburn track, next week, but this hike was hard on both of us.

Taking this trail did give us the opportunity to be in the largest, but still small, section of old growth forest in the reserve. (The photo on the left below.) We also made it out onto the beautiful beech (shown in the photo directly below the two that follow this paragraph) that is at the bottom of the catchment. And, of course, we walked through a variety of vegetation in various stages of progression from the gorse that took over the pastures once the grazing on them stopped (and which, interestingly, provides an excellent protective environment for the young, native trees that they are planting) to juvenile hardwood forest (the p hoto on the right below).

hoto on the right below).

However, we began late and the hiking took about 6 hours, so we did not leave the reserve until after 7 — a very long day. Fortunately, the days are long here and the sun doesn’t set until after 8 PM.

However, we began late and the hiking took about 6 hours, so we did not leave the reserve until after 7 — a very long day. Fortunately, the days are long here and the sun doesn’t set until after 8 PM.

Finally, just because I like them, I’ve attached two more photos. The one just below is another looking through a stand of juvenile trees. The second is of the Parakakariki headland above Otanerito Bay.